There’s an interesting relationship between historical information and the audiences intended to receive it. The transmission of that information is a phenomenon that encompasses a wide range of interactions: lecturing teachers, popular history books, museums of all shapes and sizes, and now, mobile apps.

It’s weird to slot the app experience into this pre-existing assortment of institutions, colorfully named GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) and well-established in the public eye. That these institutions are often seeking to redefine themselves is subject for another essay. For now, I posit that the public knows what a museum is. This lets them know whether or not they want to visit one, and what exactly they can expect from the experience. Museum curators also know that visitors enter their museum with pre-existing knowledge, and are pre-disposed to seek out or retain information they agree with, while avoiding or disregarding information they disagree with.

So what happens when you take this experience, and get rid of the museum’s walls? Whoops, there goes the roof, too. The cafe, the security guard, all gone. All the informational placards are now on the audience’s phone, and the exhibit is the city they live in. The exhibits are buildings, parks, empty lots, oral histories coming through your earbuds.

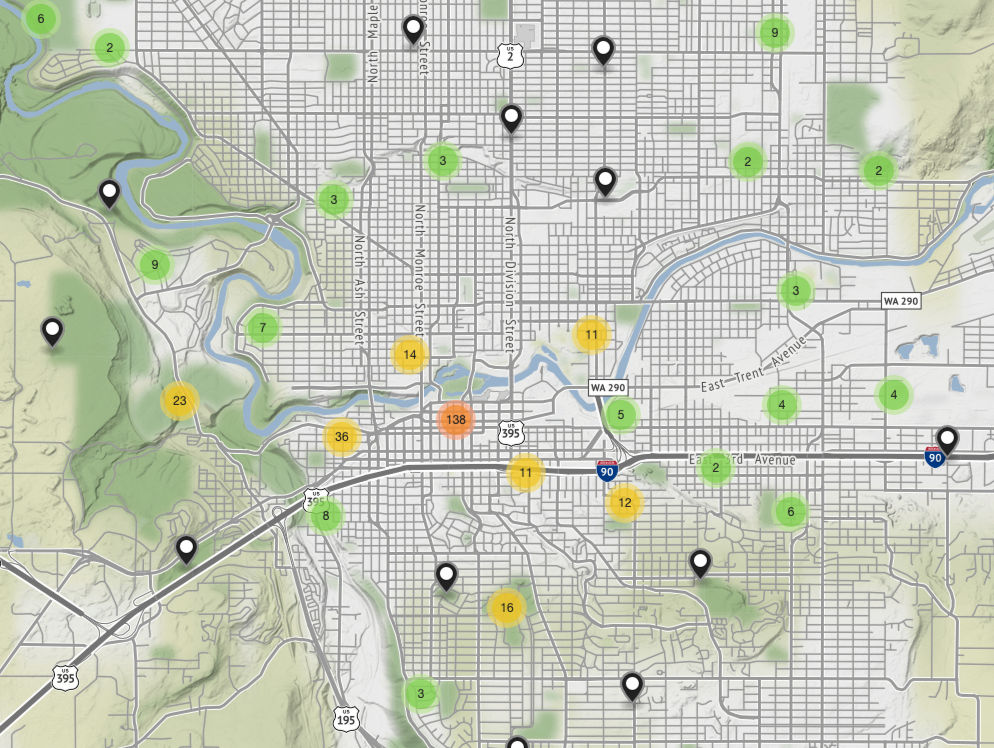

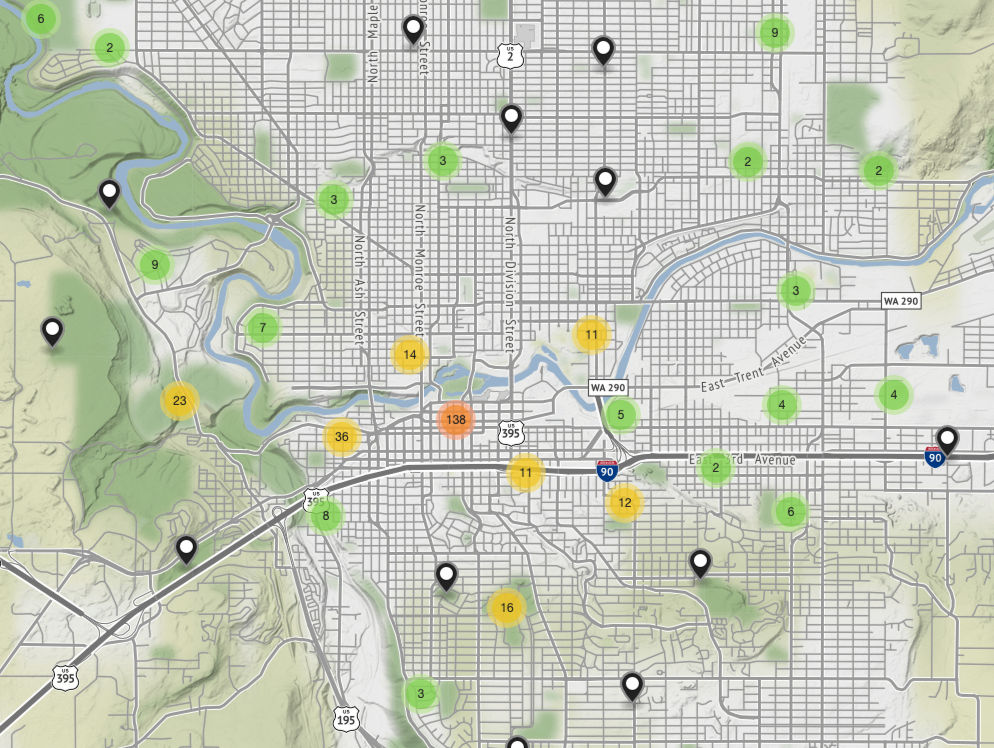

This is the world of geo-tagged, crowd-sourced history apps such as Cleveland Historical, Saltriver Stories, and Intermountain Stories. To use these websites and mobile apps is to walk a museum without walls, for better or for worse.

I will admit that I always get intensely tired in museums. I don’t know if I should blame the hushed rooms or the endless strolling, but after 30 minutes I tend to start dozing off on some uncomfortable bench. I don’t intend this as a knock against history museums, of course, but it is a notable bug of the model. (Dear reader, please tell me I’m not alone on this…)

Contrast this to driving through Spokane, pulling up articles on the “Cursed City of Spokane” while you drive past the former home of Romani Patriarch Grover Marks. Or reading about a nearby park’s former role as a massive outdoor campsite. There’s a familiarity here. An opportunity to zoom through history, skim past the dull and pick up only the shiny things: familiar places, colorful people, novel tales.

At the same time, we cannot pretend that nothing is lost by experiencing history this way. The tradeoff for publishing hundreds of micro-histories is a lower standard of curatorship. The prominence of geo-tagging minimizes narratives that don’t prominently feature a single geographic point, such as the Red Power Movement in Spokane. This emphasis on geography also occurs at the expense of temporality. Regarding stories as physical points on a map de-values their temporal relation to one another. This is not to mention the absence of any “whole” relationship to encompass all content: where a museum might expect viewers to progress through a series of rooms in unchanging order, the app user is bound by no such restrictions/guidance.

Of course, nothing is perfect. But in my opinion, the utility of history apps (and the GLAM field as a whole) is a supplementary one. No one force can simply dictate history to a person (much as my freshman history teacher may have attempted) on the contrary, our relationship with the past is constructed, individually. The stream of experiences that contribute to construct that relationship can easily accommodate an app, just as most museums could easily accommodate some sort of nap room.

So I will say that mobile history apps are not here to tear down the museums. In fact, a huge aspect of their value lays in the practice of authorship: these websites provide an accessible platform for students to practice history. For that alone, they should be highly regarded.

Another great feature is the opportunity for various forms of curatorship and storytelling. “Activist” curators can use the content of mobile history sites to present unique perspectives without facing the red tape of a pre-established, prestigious institutional inertia. And, of course, changing technology means that unique perspectives can be delivered to a (potentially) vast audience, whether those be the unheard voices of Cleveland or the remote perspectives of polar landscapes.

Hey Peter,

I definitely agree with your sentiment that history apps won’t be replacing museums anytime soon just by virtue of their innate differences. Of course, they both seek to tell history, but they do it in their own ways. History museums seek to tell history through presentation of artifacts or maybe some sort of creative design like building sets. History apps, especially like those of Spokane Historical, tell their history through location while providing supplementary materials.

That’s spot on! I’m curious how audiences feel that difference. I don’t think its a question of learning more/less, but certainly one would take away different things from the different methodologies.